1.

There’s a scene in Abbas Kiarostami’s 1974 film, The Traveler, that reminds me of the iconic spray can scene in his later masterpiece, Close-Up (1990). In the latter scene, a man kicks a spray can down a road and the camera follows it until it comes to rest, 35 seconds later. This scene has nothing, in a literal sense, to do with the plot of Close-Up. Talking about the shot in an interview, Kiarostami explained this filmmaking choice:

Well, some part of our childhood remains with us, and in my opinion, filmmaking is a reflection of our childhood. I saw a sloping street and a can lying there, an empty insecticide can. And I thought it was a good chance to play a bit…It was a chance to play around a bit. I thought we’d better kick that can down the street, because I might never again find such a nice street and empty can on such a lovely autumn afternoon.

Some of the best scenes in cinema have resulted from this sort of happenstance, where the plot does not demand what should be filmed, but the logic of the camera itself calls for an image to be captured. Because it’s “a lovely autumn afternoon” and there’s a “nice street,” and it can be filmed, it should be filmed. If the moment is let to pass, it might never present itself again, and will thus be lost forever. This in itself is a sort of childlike mentality—the spontaneous impulse that must be followed—but it’s combined with an adult’s longing to preserve the present, as the adult, unlike the child, has an understanding of past and future.

In Badlands, Terrance Malick’s debut film, a similar story explains what has come to be one of its defining shots, when Martin Sheen stands in an empty landscape at dusk, his arms hanging on a gun slung across his shoulders. Sheen said this in an interview about the scene:

The only time I recall in the film where an exterior sort of came by accident was one night we were riding home, he [Malick] was driving and I was a passenger, and we were coming home from location, and it was just about sundown and he passed the location and he said, “Oh! Oh! Oh!” and he pulled off the side of the road and he said, “Martin, walk out on that! Quickly, walk out in there,” and he went and got the camera, and he operated, and it’s the shot of Kit with the sun setting—or the moon rising, I can’t remember now—with my arms over the top of the rifle, behind my back, that shot that Terry operated…That was one that he stole, kind of. It was totally, you know, not planned, and it’s one of the best shots in the film.

Sheen is right not to remember if the sun was setting or the moon was rising, as the shot is constructed in a way to make it appear as if his character has been out on the plains all night, starting with the sun descending towards the horizon, and ending with the moon suspended in the night sky.

Interspersed with these shots of Sheen are images of wildlife—a turkey, an iguana, and a small bird. Just as with Close-Up, there is no literal reason why this scene should be included in the film, as it doesn’t advance the plot; instead, it does something with time. Talking about the spray can scene, Kiarostami said that he “had to kill some time outside” and wondered “how should we kill that time?” which led to the shot. If a film attempts to say something, it transmits its message through time, meaning through the experience of watching images unfold on a screen over two hours or so. A film, of course, cannot be reduced to its plot, but must be viewed as something like “sculpting in time,” to use Tarkovsky’s phrase, by which he meant, in one sense, “disturb[ing] the passage of time.” This is what Kiarostami and Malick are doing in these shots; they slow down time and juxtapose unexpected images with one another, which then color the film in a new way and allow for new possibilities of meaning. They invite the viewer into the film and foreground the experience of watching the film, meaning that the film cannot be reduced to summary or description but insists upon being experienced, as all great art must.

2.

Kiarostami and Tarkovsky both comment on and take seriously the audience’s understanding of their films (Malick, on the other hand, is notoriously reclusive). Kiarostami notes that, “When you make a film, due to the circumstances you’ve created, every action takes on a meaning.” This is a structuralist understanding of film—the scenes, on their own, have only one meaning, but when combined with other scenes, when existing as part of a structure, their meaning changes and multiplies due to their relation to the whole. Kiarostami continues, “Viewers help you add meaning. They help the film and themselves. So the interpretations weren’t that far off target in attributing some meaning to the can.” The film itself is only half of the equation; the other half is the experience of watching the film, and the viewer helping the director understand what they’ve created. In the introduction to Sculpting in Time, his book about filmmaking, Tarkovsky focuses on the comments he’s received from filmgoers over the years. Taken together, these few pages form an inspiring defense of art as integral to the human experience.

One letter writer, talking about Tarkovsky’s film Mirror, says, “My childhood was like that…Only how did you know about it?”

Another writes, “I am stunned by your film. Your gift for penetrating into the emotional world of adult and child.”

And another, “I've seen your film four times in the last week. And I didn't go simply to see it, but in order to spend just a few hours living a real life with real artists and real people. . . For the first time ever a film has become something real for me, and that's why I go to see it, I want to get right inside it, so that I can really be alive.”

These writers, like the viewers Kiarostami mentions, “let the film work on them,” which is how I heard someone describe Tarkovsky at a screening of Nostalghia. In contrast to these filmgoers, there are the viewers who seek to analyze the film on a literal level: “I saw your film, Mirror. I sat through to the end, despite the fact that after the first half hour I developed a severe headache as a result of my genuine efforts to analyse it, or just to have some idea of what was going on, of some connection between the characters and events and memories.”

Another writes, “The episodes in themselves are really good, but how can one find what holds them together? […] Before the film is shown the audience should be given some sort of introduction.” One can imagine a similar comment about the spray can scene in Kiarostami. If we search for a literal explanation, we are left in a confused muddle, but if we open ourselves to the experience of the film, as the woman who relates the film to her childhood does, meaning and knowledge are created.

3.

In The Traveler, the story follows a young boy obsessed with soccer. He skips school, never does his homework, and is described as “not a child, a monster” by the school headmaster. The images, however, tell a different story, one of adult indifference, as the boy is ignored and criticized repeatedly throughout the film. When he then decides to travel by overnight bus to Tehran to see his favorite soccer team, a journey that requires the deception of both his schoolmates and his parents, we understand him, and we are rooting for him (I was, at least). Both Close-Up and The Traveler, in its focus on characters who commit petty crimes to enable them to realize a dream (directing a movie, in Close-Up), reveal the way that the societies we live in prevent us from fully realizing ourselves. Sabzian, in Close-Up, and Qassem, in The Traveler, are intelligent, clever, and resourceful, but they have no outlet where they can use these abilities, and their society seems intent on preventing their flourishing. They are profoundly alienated, and their transgressions are, ultimately, an act of freedom.

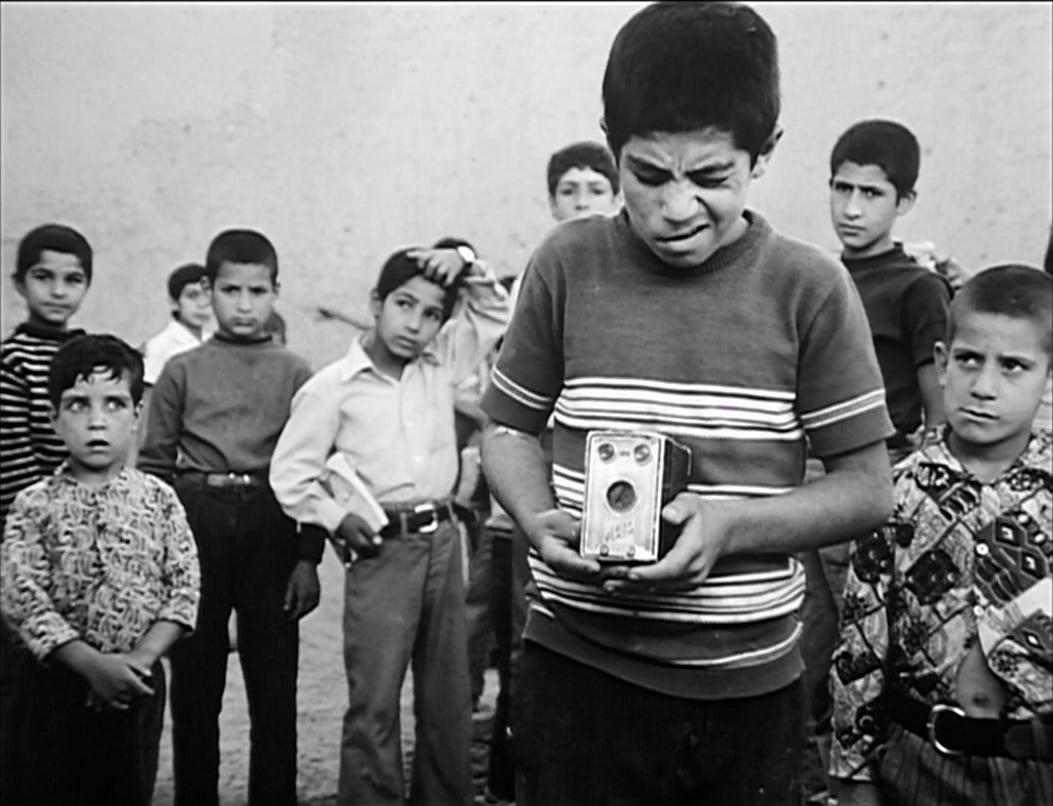

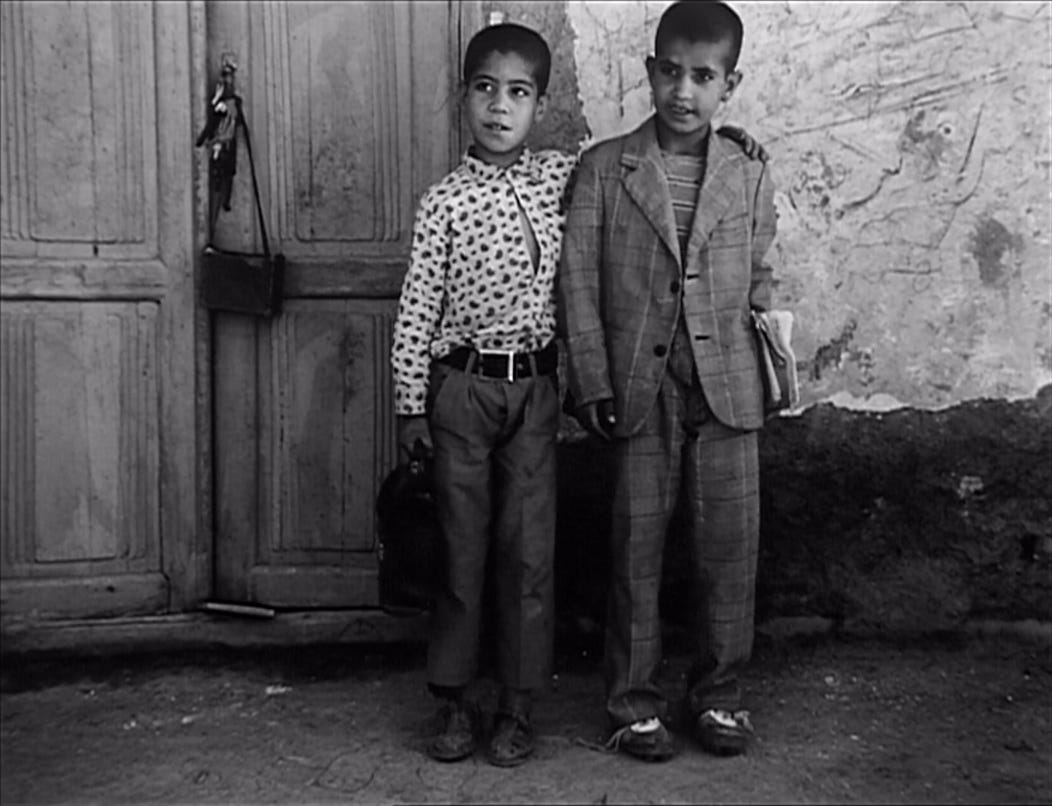

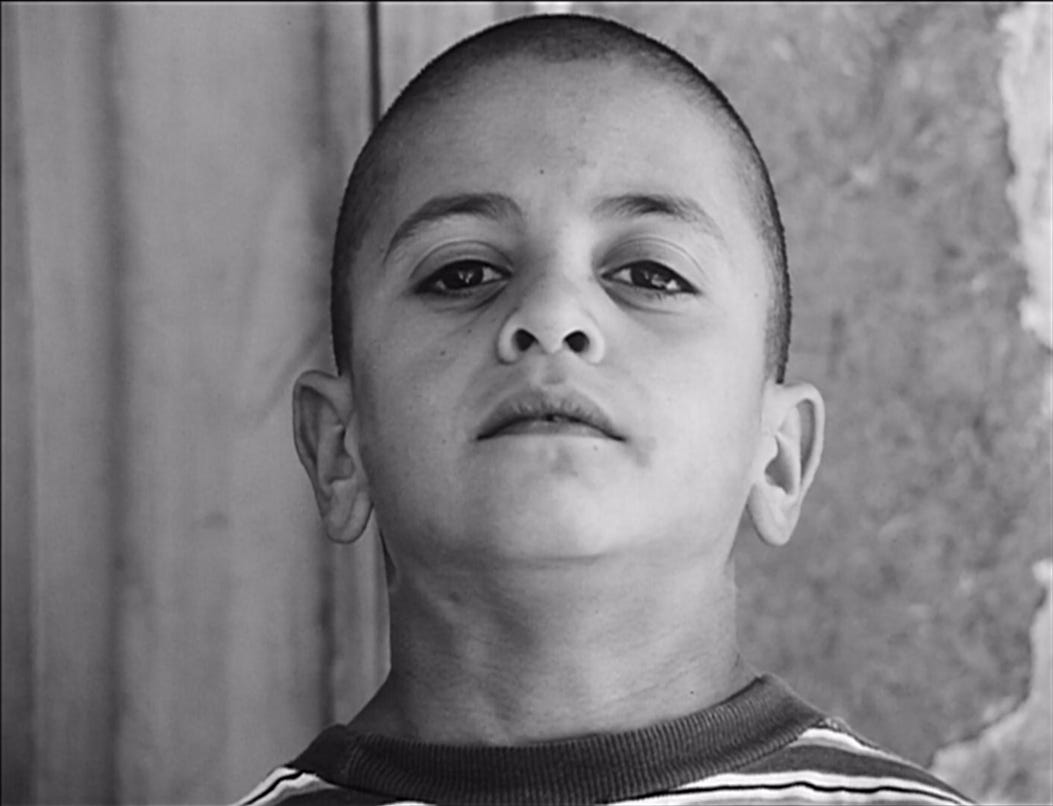

The scene that made me think of the spray can is one in which Qassem decides to trick his classmates into paying for photos of themselves. He stages a photoshoot with his friend, Akbar, so that other students will see them upon leaving school. Once they see what’s going on, they ask for photos, too, and Qassem charges them money which he will use to fund his solo trip to Tehran. The only problem is that the camera has no film. The scene starts according to the narrative demands of the film’s plot: a student arrives, hands money to Qassem, and has their picture taken. A few shots alternate—a student poses, Qassem positions the camera, Qassem’s hand goes in his back pocket with the money. But then something curious happens. It’s as if the shot that Kiarostami has composed overpowers the narrative of the film itself, and instead of the plot calling the shots, the camera itself dictates what will be on screen. First Qassem as cameraman disappears and we only see two alternating shots: the face of a photo subject, and the money going in Qassem’s pocket. Then even this disappears, and we see a succession of children’s faces (nine total), and the cuts from one face to the next become quicker and quicker. Having discovered that a child’s face is a compelling image, the film decides to show more than are logically indicated by the plot, as Kiarostami reverses this order, letting the logic of the camera itself decide what appears on screen.

Here we also realize that, although the cuts of the film make us believe that Qassem is taking these portraits, it is really Kiarostami (or his cameraman) behind the camera who is shooting these children. And even though, within the world of the film, they will be denied their pictures, outside of the film, they have been preserved as long as copies of The Traveler exist. Clearly, these are not actors but children from the town, Malayer, where the film was shot. What are we really watching here, then? Is it The Traveler, or is it a sort of documentary footage inserted into The Traveler? This type of metacinema will come to define Kiarostami, but here are the first hints. We have to remember what Kiarostami said regarding Close-Up, that “filmmaking is a reflection of our childhood,” and, to paraphrase his comment, there might have never been another opportunity for these children to be captured on film. Just as with the spray can and with Malick’s shot of Sheen, there is a spontaneous, natural feel to this scene that intuitively makes sense and, when combined with the rest of the film, takes on new meaning as part of the whole.

In the case of The Traveler, these shots foreground the fact that the film is fundamentally about childhood. Its greatest accomplishment, to my mind, is to maintain the point of view of a child for almost the entire film and to allow the viewer to remember, and possibly, relive their own childhood. I’m interested in this idea not just of recreating childhood but reliving it because it emphasizes the importance of experiencing a movie—reminding us that art cannot be summarized—and it connects to the idea of autofictionalization. This is a term coined by literary scholar Claus Elholm Andersen to refer to the technique employed by Karl Ove Knausgaard in My Struggle of “mak[ing] the past seem present by placing the literary consciousness with [the] past self.” What Andersen means is that Knausgaard does not write about his childhood from the viewpoint of his adult self, but frequently adopts the consciousness of, for example, his eight-year-old self in relating a past experience. In this way, Knausgaard is not faithful to facts—he admits in the novel that his memory is faulty and in interviews has said he made things up—but he is faithful to experience; in writing from the viewpoint of his eight-year-old self, rather than his adult self looking back to childhood, he relives rather than recreates childhood, and in the process, arrives at a higher truth by merging knowledge with experience. This is not to say facts are irrelevant, or we shouldn’t try to get them right, but it is to say that the notion of a fact divorced from its construction is just another fiction. To get to the truth of what his childhood meant, Knausgaard must become a child again, and he must allow the reader to experience this, too.

But how to relive childhood on film? The scene I’ve described above is a start, but there are other moments as well. While Qassem is being caned on the hands by the schoolmaster in his office, we watch the caning for a short time, but then the camera moves to the neighboring classroom. We see the face of his friend, Akbar, as we hear Qassem’s cries in the background. Here is the real effect of the caning, and as we see the pain and fear on Akbar’s face, and the uncomfortable teacher who attempts to go on with his lesson, we beg for Qassem to admit that he stole money (the cause of the caning), but he never does: the trip to Tehran is too important.

Eventually Qassem arrives in Tehran and finds his way to the stadium. He stands in line for five hours and is continually jostled by the other people in line—all adult men—but the camera never tilts up from Qassem, meaning that these other men are never fully visible, just their arms and shoulders. As I watched, I remembered what it was like to be small, to have to look up at others, and how it feels to move through the world as a child. Qassem never backs down, however, and he exhibits a worldliness and a remarkable sort of popular wisdom, giving as good as he gets. When he finally reaches the booth, tickets are sold out, and he and others are forcibly cleared away from the gates by police. There’s an incredible physical energy to this scene—the crowd, shot from the point of view of a child—and Qassem moves through the mass of bodies as he tries to figure out how he can see the match.

What is wonderful about this scene, as well as the photoshoot scene, is to simply see people being people. The hairstyles, the fashion, the posturing—the presentation of self in everyday life, to quote Erving Goffman’s book. In the photoshoot scene, all of the children are younger than Qassem, and they exhibit a charming naivete at the prospect of being photographed. They don’t know how to pose, and Qassem has to direct them—“Hands on your hips,” or “Bag in your other hand.” Then he really gets into it—“Smile. Show us those beautiful teeth!” and, about a baby, “What a cutie. My, you’re a chubby one!” Qassem is a natural, and he’s in his element as a showman, or, if you like, a conman. But there’s no clear distinction. Back at the stadium, Qassem discovers that he can get a ticket, but only if he pays four times the original price to a scalper. Now he is in the position of the children and must navigate a new situation. He succeeds in buying the ticket and enters the stadium, only to discover that the match doesn’t start for another three hours. So why is the stadium already half full? The fan next to him says, “Well, you have to get to your seat and settle in first.” This pre-match time functions as a sort of ritual as the fans chat and get to know one another, exchanging information about their work (“I’m a weaver. It’s not a bad living…I work independently, so I have time to come to these games…The boss can’t tell us not to go, or to go later.”), talking about players, and sharing cigarettes. Kiarostami’s other films, too, share this naturalistic quality, as the real world seemingly intrudes on the film world, allowing us to feel, like that writer to Tarkovsky, that we’ve spent “a few hours living a real life with real artists and real people.”

More writing on Kiarostami (and the spray can scene), Malick, and Tarkovsky (and Tarkovsky again)

“the film cannot be reduced to summary or description but insists upon being experienced, as all great art must.”

Such a key insight that can easily fall by the wayside when talking about art. It feels especially poignant as an artist—the amount of times a song or story have come together for me as a result of being “in the zone” or a happy accident (meaning I didn’t necessarily plan for a certain outcome) are too many to count. Summarizing and theorizing are helpful after the fact to try and understand why an experience might feel so profound (or not), but it’s not always at the forefront (though, of course, the greatest exception to what I’m saying is countered by what could be a lifetime of summarizing and theorizing and learning, all things that result in the circumstances that allow an artist to get in the zone and stumble on a particular decision (the happy accident)).

What’s interesting to me, here, is the case of the viewers analyzing the work on a literal level. Obviously some viewers will have their minds made up before entering a work, but I think an author can disarm or prime a viewer in such a way that the viewer will “let the film work on them”. This, maybe, is one of the advantages of “autofictionalization” and its variations—which, even though its all fiction, presents itself as if the imaginary wall between the work and the viewer has been removed, allowing easier access to the intended experience. Less mental gymnastics, and therefore easier to “let the film work” maybe. All interesting stuff. I haven’t seen any of these films, so I’ll be putting them on my list.

I remember being flummoxed by "Mirror" the first time I saw it, but I was also enchanted by its images and dreamlike presentation. I was aware that I was missing something, but it didn't really bother me. That said, it really is a film you won't understand on a basic "what's going on" level unless you know some Tarkovsky biographical background and something about life in the USSR during the period being depicted.